from 01.01.2000 to 01.01.2006

Vladivostok, Russian Federation

Russian Federation

Russian Federation

UDC 656.6

Container transportation is an integral part of international trade. Thanks to the standardization of containers and a well-developed logistics infrastructure, they ensure fast, reliable and cost-effective delivery of a variety of goods between countries and continents. Containerization helps optimize transport chains, reduce costs, and simplify customs procedures, making it a key element of the global economy. The cargo plan for a particular commercial vessel is fundamental from the point of view of safety, because its incorrect filling has the highest degree of impact on the safe transportation of goods. As the share of container traffic in the total cargo turnover is continuously increasing, the problem of shippers incorrectly declaring the actual weight of containers is becoming more urgent. Incorrect declaration of container weight may be due to the shipper's desire to save money on cargo transportation, as well as to an erroneous estimate of cargo weight, or to a failure to account for the weight of cargo containers, separation materials, etc. Overloaded containers or containers with incorrectly specified weights pose serious problems from the point of view of ensuring the safety of the transport vessel – they can lead to loss of stability of the vessel, increasing the risk of collapse of stacks, as well as transshipment equipment for container handling, creating danger during loading and unloading in ports and warehouses. If discrepancies in weight are found, containers can be detained at ports or returned to the shipper. The main causes and consequences of incorrect declaration of container weight are considered.

safety of navigation, accidents, container transportation, container weight, cargo

Introduction

Currently, more than 6 300 container ships are continuously plying the oceans and other waterways, transporting cargo around the world. The range of cargo types transported in containers is noticeably expanding: it has become possible to ship the small batches liquid and bulk cargo in cargo transport units (CTU) as a result of the introduction of flexitanks and tank containers. Container transportation takes up an increasing share of the total cargo turnover due to the versatility in relation to the shipping cargo. An important advantage of the container method of cargo delivery is versatility in multimodal transportation. This advantage is more noticeable as longer the chain of delivery means from the supplier to the recipient.

Over the past 60 years the container capacity of ships has increased from 400 to approximately 19 500 containers (in conventional TEU), i.e. almost 50 times. Currently the largest container ships cost more than $150 million, and the cargo they carry can cost several billion US dollars at a time.

To make up a cargo plan is the biggest problem in container transportation. The distribution of cargo affects the vessel stability, which is directly related to the safety of navigation. Incorrect arrangement of containers on the vessel can lead to damage, loss of cargo, complete loss of stability and sinking of the vessel, and loss of the crew. Therefore, planning and proper loading of ships is an important tool to ensure the safe operation of the vessel [1].

A serious safety issue is the inaccuracy of the cargo containers weight measuring. Frequently, shippers estimate the particular consignment weight lower than the actual weight [2-4]. The reasons for this can be different. It happens that shippers calculate the size of the consignment based on the product data, but do not take into account the weight of transport packaging, separation materials, pallets and other auxiliary materials. In addition, the cost of transportation directly depends on the cargo weight, what encourages shippers to declare a weight lower than the actual weight.

The consequences of the incorrect information receiving of the container weight may be:

1. Incorrect cargo plan, what may have the following consequences:

– insufficient stability of the vessel, leading to large angles of list or capsizing;

– dangerous bending and torsion loads on the hull, which may lead to deformation or breakage of the vessel.

2. Difficulty in the handling equipment operation and the associated risks:

– removal and re-loading of containers (and the associated delays and costs) if excess weight is detected;

– risk of workers injury during loading and unloading operations.

3. Economic losses:

– disruption of the transport processing schedule and the entire supply chain of properly declared containers;

– losses in the accident event.

Container weighing inaccuracies can occur at any stage of the shipping process from initial loading to final delivery. Some of the causes of incorrect weight readings include:

1. Lack of uniform standards regarding the scales used: their accuracy and operating principle.

2. Human error: the operators who handle the weighing process may make errors in recording or interpreting weight data due to carelessness, lack of training, or a misunderstanding of the correct procedure.

Below are details of the investigations into the CMA CGM George Washington (MAIB investigation), President Eisenhower (NTSB investigation), MSC Zoe (DHS investigation) and other wrecks.

Materials and methods of the investigation

Overloaded containers or containers with incorrectly declared weights have historically created problems for both the carrier and the handling equipment when such containers handling [5, 6].

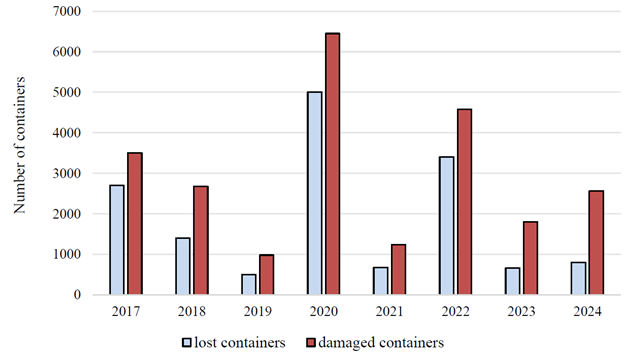

According to the World Shipping Council [7], in 2024, an estimated 576 containers were lost at sea out of approximately 250 million transported. While this represents an increase from 221 containers lost at sea in 2023, it remains well below the 10-year average of 1 274. In 2022, 661 containers were lost at sea. This represents less than one thousandth of 1% (0.00048%) of the roughly 250 million packed and empty containers currently shipped each year, with cargo transported valued at more than $7 trillion. Reviewing the results the WSC estimates that there was on average a total of 1 566 containers lost at sea each year. The average losses for the last three years were 2 301 containers per year. Statistics on the number of damaged and lost containers for the period 2016-2024 are shown in the Figure.

Statistics on the number of damaged and lost containers for the period 2016-2024

This increase of loss is due to factors such as increasing ship sizes, extreme weather conditions and incorrectly declared cargo weights (resulting in container stack collapses). On large container ships the stack height can reach 26 m. Heavy loads are created on the lower tiers of containers and fastening systems in heavy seas conditions [8-10].

Corrosion degradation and operational wear of fastenings lead to the fact that those containers whose weight does not exceed the established standards are often lost in intense rolling conditions. Exceeding the permissible containers weight initially lays the foundation for an emergency.

The container ship MOL Comfort accident is example of how misdeclared cargo can lead to an incorrect cargo plan, which can cause excessive hull deformation in rough seas. On 17 June 2013, the MOL Comfort, carrying 4 382 containers, broke into two and sank while 200 miles off the coast of Yemen. Some containers fell into the sea, some sank with the stern of the ship, and some were destroyed by a fire in the bow of the ship, which was still afloat. Evidence was lost along with the lost cargo, but the official investigation considered the possibility that misdeclared cargo contributed to the incident. The examined sister ships data showed both under- and overweight containers [6, 7, 11].

Incorrect reported weights can cause a stack to collapse even in calm port conditions. In February 2007, a stack of containers on the container ship Limari collapsed in the port of Damietta, Egypt, due to excessive weight. The captain’s incident report to the authorities noted that excessively heavy containers were loaded on the upper tiers and the maximum stack weight was significant exceeded in some rows. The excessive containers weight placed excessive stress on the lashings. In addition, excessively uneven weight distribution and/or exceeding the maximum weight in any stack will result in excessive stress on the stacking/securing elements and excessive stress on the containers. The actual weight of the containers was determined using devices on the gantry cranes when lifting and moving the collapsed containers. The actual weight of the containers exceeded the declared weight by 362% (row 08), 393% (row 06), 407% (row 04) and 209% (row 02) in row 52, where the collapse occurred [12].

Let us recall some incidents involving the loss of con tainers at sea, which received wide resonance in the press (Table).

Some of the accidents involving the loss of a large number of containers

|

Date |

Ship name |

Accident |

Number of lost containers |

|

06/02/2024 |

President Eisenhower |

Collapse of stacks |

23 |

|

24/05/2020 |

APL England |

Collapse of stacks |

50 |

|

01/06/2018 |

Yang Ming Marine Transport |

Collapse of stacks |

81 |

|

20/01/2018 |

CMA CGM G. Washington |

Collapse of stacks |

137 |

|

14/02/2014 |

Svendborg Maersk |

Collapse of stacks |

More than 500 |

|

17/06/2013 |

MOL Comfort |

Fracture and flooding |

4 293 |

|

11/06/2011 |

Deneb |

Capsizing a ship |

– |

|

18/01/2007 |

MSC Napoli |

Collapse of stacks |

103 |

|

February 2007 |

Limari |

Collapse of stacks |

– |

|

27/01/2007 |

P&O Nedlloyd Genoa |

Collapse of stacks |

27 |

Discussion

In 2014 the International Maritime Organization (IMO) adopted rules on container weight verification, which amended Chapter VI of the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS 1974) [11]. It noted that misdeclaration “represents the most significant risk” to container shipping, leading to major losses. The adopted rules focus on “overweight” containers, where the declared weight is less than the actual weight. Containers overloaded beyond their declared capacity are a problem particularly for 40-foot containers, which can be overloaded even when carrying moderately dense cargo. Under the current rules, containers exceeding their declared capacity cannot be loaded on board a ship (SOLAS 1974: Annex, Regulation VI 5 (5). The new obligation is to weigh the container or its contents and declare that weight.

The Verified Gross Mass (VGM) regulation, which came into force in 2016, was intended to significantly reduce the risk of incorrectly declared weights in container shipping, which can lead to stack collapses and dangerous stability issues. A recent incident involving a US-flagged container ship, where an incorrectly declared weight resulted in a stack collapse and the loss of 23 containers, highlighted the potential dangers that still exist when incorrect weights are entered into booking systems and containers are not re-weighed before loading.

Shipmasters have primary responsibility for the safety of the ship, including the cargo. They may also be responsible for the container weight. However, the IMO Sub-Committee on Dangerous Goods, Solid Cargo and Containers considers that it is not practical to assign shipmasters primary responsibility for container weight, because they do not have the technical capacity to check the weight. Furthermore, cargo shipments are planned and prepared for loading on board ships well in advance in order to minimise the time the ship spends at berth. It would be highly inefficient to perform check weighing during loading. Although checking the weight is the responsibility of the shipmaster, most modern container ships do not have lifting equipment, so shipmasters must rely on others to fulfil their general safety responsibilities.

Placing responsibility for the accuracy of container weight declaration on the shipper does not solve the problem in the case of deliberate misrepresentation. This type of misrepresentation can only be detected if an uninterested party carries out the control.

Ports are obvious points where container weights can be controlled, because all containers transported by sea pass through them and container handling is carried out using shore cranes. However, involving ports in the container weight control process creates an additional party in the distribution of responsibility between the shipper and the ship's master occurred [13]. It also expand the scope of IMO's interest in ports, since the shipping contract is concluded between the shipper and the shipping company, and not between the shipper (or ship) and the port.

It is obvious that misdeclaration occurs on land (before loading onto a vessel). The danger of the consequences of misdeclaration for shipping should mean that all parties must comply with the rules.

Conclusion

The problem of weights misdeclaration is serious, leading to loss of vessels and cargo. Everyone involved in the container shipping industry understands that declaring the correct weight of containers improves the safety of container ships, their crews, and shore personnel involved in handling and shipping containers occurred [14, 15]. The current IMO weight control regulations alone are not an absolute protection against this problem. A “chain of responsibility” approach, where all parties involved in the shipping process contribute, is proposed as a way forward.

Currently, most specialized container terminals have automatic weighbridges occurred [16]. If the container cargo weight is not permissible, the master will refuse the container, so it is recommended to carefully read the maximum weight indicated on the container before loading to avoid the need to reload. Recording incidents of false information about container loading and taking administrative action against persistent offenders would go a long way towards solving the problem.

1. Carik R. S. Kompleksnyj podhod k bezopasnosti morskih kontejnernyh perevozok [An integrated approach to the safety of container shipping]. Mir transporta, 2016, vol. 14, no. 3 (64), pp. 212-231.

2. Tonkonog V. V., Filatova E. V., Golovan' T. V. Problemnye voprosy zanizheniya vesa gruza v kontejnerah, pere-meshchaemyh morskim transportom [Problematic issues of underestimating the weight of cargo in containers transported by sea]. Putevoditel' predprinimatelya, 2018, no. 40, pp. 268-288.

3. Malikova T. E., Filippova A. I. Razrabotka sistemy slezheniya za importnymi gruzopotokami, oformlyaemymi po tekhnologii predvaritel'nogo informirovaniya v morskom punkte propuska [Development of a system for tracking imported cargo flows processed using the technology of pre-formation at a sea checkpoint]. Morskie intellektual'nye tekhnologii, 2016, no. 4-2 (34), pp. 32-36.

4. Yanchenko A. A., Malikova T. E. Metodika analiza technologicheskogo processa obrabotki gruza na kontejnernom terminale [Methodology for analyzing the technological process of cargo handling at a container terminal]. Ekspluataciya morskogo transporta, 2020, no. 2 (95), pp. 20-26. DOIhttps://doi.org/10.34046/aumsuomt95/3.

5. Oficial'nyj sajt Soveta po bezopasnosti na transporte Yaponii (JTSB) [Official Website of the Japan Transportation Safety Board (JTSB)]. Available at: https://www.mlit.go.jp/jtsb/english.html (accessed: 24.04.2025).

6. Oficial'nyj sajt Otdeleniya po rassledovaniyu morskih proisshestvij (MAIB) [Official website of the Maritime Accidents Investigation Branch (MAIB)]. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/marineaccident-investigation-branch (accessed: 24.04.2025).

7. Oficial'nyj sajt Vsemirnogo soveta sudohodstva [The official website of the World Shipping Council]. Available at: https://www.worldshipping.org/ (accessed: 24.04.2025).

8. Gannesen V. V., Solov'eva E. E. Avarijnost' morskih sudov i metodologiya poiska prichinno-sledstvennyh svyazej, privedshih k avarii [The accident rate of marine vessels and the methodology of searching for cause-and-effect relation-ships that led to the accident]. Nauchnye trudy Dal'rybvtuza, 2022, vol. 61, no. 3, pp. 70-76.

9. Drewry Container Trade Statistics. Available at: https://www.drewry.co.uk/ (accessed: 13.04.2025).

10. Solov'eva E. E., Gannesen V. V. Tendencii avarijnosti morskih sudov [Marine accident trends]. Nauchnye trudy Dal'rybvtuza, 2022, vol. 62, no. 4, pp. 118-125.

11. Oficial'nyj sajt Mezhdunarodnoj morskoj organizacii [Official website of the International Maritime Organization]. Available at: https://https://www.imo.org/ (accessed: 04.05.2025).

12. Containers Lost at Sea, World Shipping Council. Available at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5ff6c5336c885a268148bdcc/t/6667a1b5a8b88c3efac6665e/1718067641677/Containers_Lost_at_Sea_2024_FINAL.pdf (accessed: 13.04.2025).

13. Chernova A. I., Avdon'kin S. V. Sovremennoe sostoyanie i puti sovershenstvovaniya organizacii obespecheniya bezopasnosti moreplavaniya kontejnerovozov [The current state and ways to improve the organization of ensuring the safety of navigation of container ships]. Transportnoe delo Rossii, 2013, no. 2, pp. 38-40.

14. Petrova E. E., Gannesen V. V. Analiz opyta avtomatizacii i robotizacii operacionnyh processov kontejnernogo terminala [Analysis of the experience of automation and robotization of container terminal operational processes]. Nauchnye problemy vodnogo transporta, 2024, no. 78, pp. 178-190. DOIhttps://doi.org/10.37890/jwt.vi78.439.

15. Malikova T. E., Yanchenko A. A. Primenenie tekhnologii predvaritel'nogo informirovaniya tamozhennyh organov pri morskih vneplanovyh gruzoperevozkah [Application of the technology of preliminary informing of customs authorities during sea unscheduled cargo transportation]. Vestnik Gosudarstvennogo universiteta morskogo i rechnogo flota imeni admirala S. O. Makarova, 2016, no. 3 (37), pp. 33-45. DOIhttps://doi.org/10.21821/2309-5180-2016-7-3-33-45.

16. Azovcev A. I., Malikova T. E., Filippova A. I., Yanchenko A. A. Razrabotka infologicheskoj modeli bazy dannyh predvaritel'nogo informirovaniya tamozhennyh organov dlya sudohodnoj kompanii [Development of an infological database model for preliminary information of customs authorities for a shipping company]. Morskie intellektual'nye tekhnologii, 2016, no. 3-1 (33), pp. 327-332.