Россия

Предложена концепция модульной контейнерной верфи, разработанная для повышения мобильности и экономической эффективности производства безэкипажных катеров, что особенно актуально в условиях необходимости оперативного развертывания производственных мощностей для нужд обеспечения защиты Российской Федерации. Предлагается инновационный подход к судостроению, основанный на использовании стандартных 20- и 40-футовых контейнеров, каждый из которых имеет строгую специализированную производственную или вспомогательную функцию. Рассмотрены основные преимущества модульной верфи, включая мобильность (возможность быстрого развертывания в различных локациях), масштабируемость (адаптация производственных мощностей к меняющимся потребностям), экономическую эффективность (снижение капитальных и операционных затрат) и быстрое развертывание (сокращение сроков введения в силу устойчивости верфи). Проанализированы применимые ограничения, такие как нехватка квалифицированных кадров и сложности материально-технического снабжения, и определены пути их преодоления. Представлена базовая конфигурация модульной верфи, включающая зону для складирования, подготовки материалов, формования и ламинирования, сборки корпуса, электро- и механического монтажа, установки датчиков, тестирования и доводки, а также административно-управленческих блоков. Приведены предварительные технико-экономические показатели (CAPEX и OPEX) для расчета верфи, ориентированной на нужды Министерства обороны РФ, и проведен анализ чувствительности основных показателей эффективности к изменениям стоимости и экономическим затратам, что приводит к их лидерству на прибыльности проекта. Сформулирован вывод о высокой инвестиционной привлекательности модульного предложения по сравнению с капитальным строительством стационарных верфей, а также о значительном потенциале для дальнейшего развития и с учетом данной концепции.

безэкипажный катер, модульное производство, контейнерная верфь, судостроение, мобильность, технико-экономическое обоснование, логистика, анализ чувствительности

Introduction

In the context of the current geopolitical situation and the increasing significance of maritime spaces, ensuring the security of sea borders and protecting the national interests of the Russian Federation are priority tasks. Unmanned boats (UBs) play an important role in solving these tasks, designed to perform a wide range of operations, including patrolling, reconnaissance, detection and destruction of surface and underwater targets, protection of port waters and important infrastructure facilities. Unmanned boats are a specialized, reusable device with dimensions up to 11 meters in length, 2 meters in width, and 1.9 meters in height [1-4].

The relevance of this research is due to the need to create efficient and flexible production facilities to meet the needs of the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation for modern UBs. Traditional approaches to shipbuilding, based on the construction and operation of large stationary shipyards, are characterized by high capital intensity, long construction times, dependence on infrastructure, and limited mobility [5].

Research objective: to develop and justify a concept for a modular container shipyard that ensures high operational efficiency and economic efficiency in the production of UBs for the needs of the defense industry.

Review of existing approaches and justification of the concept

An analysis of existing methods for organizing shipbuilding production shows that traditional shipyards do not always meet the requirements for deployment speed and mobility [6], especially in a rapidly changing geopolitical environment. Alternative approaches exist, such as block shipbuilding, but they also require significant capital investment and infrastructure.

The concept of a modular container shipyard represents an innovative approach that overcomes the limitations of traditional methods. The basis of the shipyard is standardized 20- and 40-foot shipping containers, adapted to perform individual technological operations. This approach provides:

– mobility: the shipyard can be quickly deployed anywhere there is access to a body of water and the ability to connect to electricity and other utilities;

– scalability: production capacity is easily adapted to changing needs by adding or removing containers;

– economic efficiency: reduced capital costs through the use of ready-made modules and the optimization of technological processes;

– rapid deployment: the time to commissioning is significantly reduced compared to the construction of a traditional shipyard.

Methodology: structure and technological flow of the modular shipyard

The implementation of the modular container shipyard concept involves the formation of a production complex consisting of interconnected specialized modules.

Structural organization

The basic configuration of the shipyard (estimated production capacity of 10-15 UBs per year) includes the following key functional areas (Table 1).

Table 1

Functional structure of the modular container shipyard

|

Zone (module) |

Typical container |

Key function |

Equipment (examples) |

|

Raw material warehouse |

2×40-ft HC |

Storage and accounting of composite materials, metal, components |

Shelving, accounting system (QR codes/RFID), forklift, scales, electric stacker |

|

Material preparation |

1×40-ft HC |

Cutting, trimming |

Automated cutting machine, plasma cutting machine, milling machine |

|

Raw material warehouse |

2×40-ft HC |

Storage and accounting of composite materials, metal, components |

Shelving, accounting system (QR codes/RFID), forklift, scales, electric stacker |

|

Material preparation |

1×40-ft HC |

Cutting, trimming of composites and metal |

Automated cutting machine, plasma cutting machine, milling machine |

|

Molding / laminating |

1×40-ft HC |

Vacuum forming, laminating, temperature control |

Vacuum bags, thermochambers, resin supply systems |

|

Hull assembly |

2×40-ft HC |

Assembly of hull sections, connecting elements, grinding, sealing |

Slipways, lifting mechanisms, welding equipment |

|

Electrical installation |

1×20-ft HC |

Laying cables, installing electronics, checking electrical circuits |

Electrician workstations, measuring instruments, testing equipment |

|

Mechanical installation |

1×20-ft HC |

Installing engines, propulsion systems, steering, mechanical units |

Tools, equipment for installing engines, shafts of various compositions, propellers |

|

Sensor installation |

1×20-ft HC |

Mounting navigation equipment, sensors, cameras, control systems |

Workstations, tools, calibration equipment |

|

Testing and finishing |

1×40-ft HC |

Testing, calibration, painting, final assembly |

Test benches, checking the alignment of the shaft line, paint booth, external environment simulators |

|

Administration, management and auxiliary |

2×20-ft HC + 1×40-ft HC |

Office, quality control, workshop, power unit, sanitary and domestic module, control and design center |

Office furniture, measuring equipment, diesel generator, compressors |

Each container is a specialized module, optimized for performing specific technological operations [7]. Automation and robotization of technological processes allow for increased productivity, reduced labor costs, and ensuring high product quality.

Technological flow

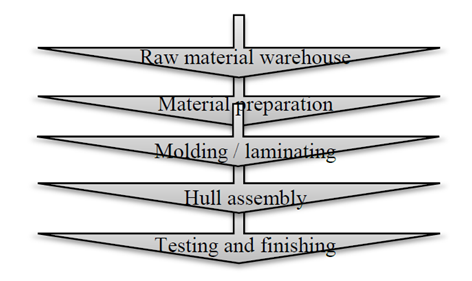

The technological flow of UB production at the modular shipyard is organized according to the principle of a linear-parallel structure (Fig. 1). Materials enter the raw material warehouse, where they undergo incoming inspection. Then the raw materials go to the preparation area, where cutting and processing are carried out. Workpieces are transferred to the molding area, where hull elements are formed. Finished elements are assembled into hull sections, which are then joined in the assembly area. At the next stages, equipment installation, electrical installation, mechanical installation, and sensor installation take place. At the final stage, tests, finishing, and painting are carried out.

Fig. 1. Diagram of the UBs production process at the modular shipyard

A key element in increasing efficiency is the organization of continuous quality control at each stage of production [8]. This allows for the timely identification and elimination of defects, as well as ensuring that the products meet the requirements of the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation.

Deployment times

An estimate of the time for deploying a modular shipyard (taking into account the parallelization of work) shows that realistic commissioning times are 12-20 weeks. This includes:

– 14 days: transportation of containers to the site;

– 4 days: installation of containers and site preparation;

– 2 days: connection to the power supply;

– 1 day: connection of water supply and sewage;

– 30 days: configuration of equipment and software (estimated value, may vary);

– 6 days: testing and calibration;

– 5 days: additional time for unforeseen delays.

Technical and economic justification

To assess the economic efficiency of the proposed concept, an analysis of capital (CAPEX) and operating (OPEX) costs was conducted.

CAPEX assessment

The CAPEX assessment is based on an analysis

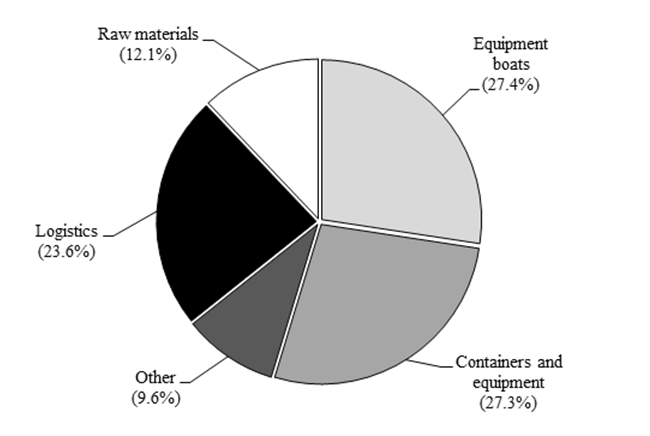

of the cost of equipment and site preparation expenses [9]. The basic configuration of the shipyard (14 containers) will require an investment of 42 790 000-114 920 000 rubles (Table 2). Within the framework of the technical and economic justification, the main components influencing CAPEX were analyzed (Fig. 2).

Table 2

Budget for the deployment of a container shipyard, rub.

|

Item |

Minimum estimate |

Maximum estimate |

|

Containers and equipment |

11 050 000 |

31 400 000 |

|

Purchase of boat equipment (first year) |

21 000 000 |

31 500 000 |

|

Purchase of raw materials (first year) |

5 990 000 |

13 920 000 |

|

Launch logistics (Auto/Rail/SMP) |

600 000 |

27 100 000 |

|

Design, documentation, commissioning |

650 000 |

1 500 000 |

|

Site infrastructure (foundation, utility connections) |

2 000 000 |

5 000 000 |

|

IT Infrastructure (servers, software, licenses) |

1 000 000 |

3 000 000 |

|

Security systems (fire, security, video surveillance) |

500 000 |

1 500 000 |

|

Total |

42 790 000 |

114 920 000 |

Fig. 2. Structure of capital expenditures (CAPEX)

OPEX assessment

The assessment of operating costs (OPEX) includes costs for raw materials, materials, wages, electricity, equipment maintenance, and other expenses. A preliminary estimate of annual operating costs is 79 490 000-138 120 000 rubles (Table 3).

Table 3

Analysis of operating expenses (OPEX) considering projected inflation, rub.

|

Year |

OPEX min |

OPEX max |

CAPEX min |

CAPEX max |

Total min |

Total max |

|

1 |

79 490 000.0 |

138 120 000.0 |

42 790 000.0 |

114 920 000.0 |

122 280 000.0 |

253 040 000.0 |

|

2 |

83 464 500.0 |

145 026 000.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

83 464 500.0 |

145 026 000.0 |

|

3 |

87 637 725.0 |

152 277 300.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

87 637 725.0 |

152 277 300.0 |

|

4 |

92 019 611.0 |

159 891 165.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

92 019 611.0 |

159 891 165.0 |

|

5 |

96 620 592.0 |

167 885 723.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

96 620 592.0 |

167 885 723.0 |

|

Total |

439 232 428.0 |

763 200 188.0 |

42 790 000.0 |

114 920 000.0 |

482 022 428.0 |

878 120 188.0 |

Sensitivity analysis

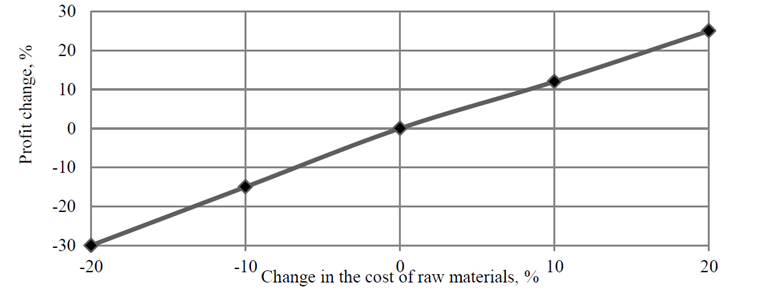

Sensitivity analysis revealed that the most sensitive parameters to changes in profitability are the cost of raw materials (±20%), logistics costs (which significantly increase annual operating expenses), and productivity (the volume of boat output) (Fig. 3). A financial planning model was constructed to reflect changes in key indicators with variations in crucial variables.

Fig. 3. Project sensitivity analysis to raw material costs

Logistics and risk management

Logistics and risk management logistics is a critical element for the successful implementation of the project [10]. A detailed logistics strategy has been developed to ensure uninterrupted supply of raw materials, materials, and equipment, including:

1. Selection of optimal suppliers: priority is given to Russian suppliers, which reduces currency and sanctions risks (Table 4).

2. Long-term contract strategy: fixing prices and delivery times, especially for critical components.

3. Development of a warehouse network: organizing storage warehouses near ports and major logistics centers.

4. Reserving strategy: storing reserves of materials and components in case of unforeseen delays.

5. Route optimization: utilizing multimodal transportation, including the Northern Sea Route where logistically appropriate.

Table 4

Approximate list of suppliers of raw materials and equipment

|

Raw material |

Supplier |

Delivery times |

|

Fiberglass and carbon fiber |

JSC Kamenskvolokno (Kamensk-Shakhtinsky) |

2-6 weeks |

|

Resins (epoxy, polyester) |

JSC Pigment (Tambov), LLC Novochim (Perm) |

2-5 weeks |

|

Fillers (sand, aluminum powders) |

Silicon CJSC (Bratsk) |

4-8 weeks |

|

Engines |

PJSC Zvezda (Saint Petersburg), JSC Kolomna Plant (Kolomna) |

6-12 months |

|

Control systems |

Concern Avtomatika JSC, Research Institute Vector JSC (Saint Petersburg) |

4-12 months |

|

Electrical and lighting, navigation equipment, control systems |

Various suppliers |

3-12 months |

To manage risks, a system has been developed that includes:

– cargo and property insurance;

– reserving critical components;

– thorough supplier selection considering their reliability and reputation;

– systematic monitoring of the production process and logistics.

Business model

The optimal business model is a combined approach that includes:

1. State contract: production and supply of UBs within the framework of state defense orders, ensuring stable income and financing.

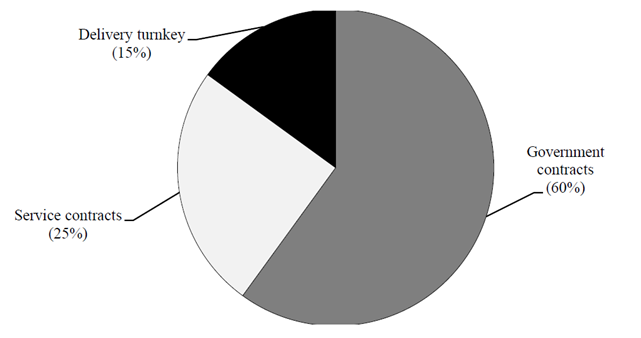

2. Turnkey supply and service contracts: providing a full range of services, including development, production, personnel training, warranty, and after-sales service of UBs. This approach ensures flexibility, risk diversification, and business sustainability. The revenue structure is shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Revenue structure

The proposed business model is based on a hybrid approach, encompassing the fulfillment of state defense orders to ensure stable income, and the provision of comprehensive “turnkey” solutions, including development, production, personnel training, and subsequent servicing. This hybrid strategy ensures business resilience, risk diversification, and adaptability to the changing needs of customers in the defense sector.

Conclusion

The presented concept of a modular container shipyard for serial production of UBs demonstrates high potential efficiency and competitiveness. It provides:

– rapid deployment: the shipyard is ready for operation within 2.5-4 months;

– high mobility: relocation to new sites in a short period;

– economic efficiency: reduction of capital costs and optimization of operating expenses;

– scalability: the ability to increase production capacity in accordance with customer needs.

The implementation of this project will create a modern production base for the output of UBs that meets the requirements of the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation and will make a significant contribution to strengthening the country’s defense capabilities. Further research requires detailing engineering solutions, conducting additional economic calculations, and developing a detailed project management plan.

1. Абронкин Ю. А. Модульная постройка судов. СПб.: Судостроение, 2005. 312 с.

2. Быховский И. А. Корабельных дел мастера. М.: Судпромгиз, 1961. 216 с.

3. Войтов Д. В. Подводные обитаемые аппараты. М.: АСТ; Астрель, 2002. 302 с.

4. Гуляев Э. Е. Исследования Реда и Иэтса местной крепости судовых переборок и обшивок под давлением воды. СПб.: Изд-во Мор. техн. ком., 1892. 148 с.

5. Время. Люди. Корабли. Исторический обзор 2006−2010 гг. / Конструктор. бюро «Вымпел». Н. Новго-род: Бегемот, 2010. 176 с.

6. Павлов А. Б. Судостроение России: проблемы и перспективы развития // Судостроение. 2018. № 4. С. 12–21.

7. Bagazinski N. J., Ahmed F. ShipGen: A Diffusion Model for Parametric Ship Hull Generation with Multiple Objectives and Constraints // Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2023. N. 11 (12). P. 2215. DOIhttps://doi.org/10.3390/jmse11122215.

8. Zhang L., Ji X., Jiao Ya., Huang Yi., Qian H. Design and Control of the “TransBoat”: A Transformable Unmanned Surface Vehicle for Overwater Construction // IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics. 2023. V. 28. Iss. 2. P. 1116–1126. DOIhttps://doi.org/10.1109/TMECH.2022.3215506.

9. Bagazinski N. J., Ahmed F. Ship-D: Ship Hull Dataset for Design Optimization using Machine Learning // ASME 2023 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference. URL: https://decode.mit.edu/assets/papers/ShipD_Dataset_Bagazinski_and_Ahmed_2023.pdf (дата обращения: 02.09.2025).

10. Khan S., Goucher Lambert K., Kostas K., Kaklis P. ShipHullGAN: A generic parametric modeller for ship hull design using deep convolutional generative model // Comput-ers Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering. 2023. N. 411 (11). P. 116051. DOIhttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.cma.2023.116051.