Russian Federation

Russian Federation

Russian Federation

Russian Federation

Species diversity is usually considered one of the key factors that takes into account the number of different species in an ecosystem – the so-called biological diversity found in the environment. It consists of two components: species richness and uniformity. In this context, the physico-chemical parameters were analyzed and a list of 2,322 individuals was compiled, divided into 28 families and 34 species that are often found in the Cotonou estuary. The accepted methodological approach revolves around data collection, real-world research, data processing, and results analysis. The sample sizes varied depending on climatic and meteorological factors. The data were obtained as a result of sample surveys for the period from September 2019 to May 2020. Indicators of diversity are the Shannon–Weaver diversity indices, the Pieloux uniformity indices, and the frequency of occurrence. These indices range from 3.49 to 4.6 bits, from 0.69 to 0.85 and from 12 to 88%, respectively, which indicates a high diversity of the population of the studied environment. Communities of three stations are identified: one corresponds to a shallow part with a depth of less than 2 m, the second is located in the middle of the front line of a moderately deep mouth, and the third is deeper than the other two, located on a site near the port of Cotonou. During the study period, changes in the diversity indices reflect changes in the total abundance and structure of biomass. An increase in the indices is associated with a reduction in this structure and is not necessarily a sign of an improvement in the ecosystem due to various reasons for the rarity or extinction of certain endemic species.

specific diversity, ecosystem, station, Cotonou

Introduction

All bodies of water due to their great faunal wealth constitute laboratories of great interest for the study of animal communities. These aquatic animals (fish, crustaceans, mollusks, etc.) which are found abundantly in both continental and marine ecosystems, constitute a large source of protein for the world population [1]. Thus, aquatic ecosystems constitute not only sources of wealth but also real sources of Life and therefore are very important for the conservation of biodiversity [2]. Among these ecosystems include estuarine ones which are dynamic and environmentally complex systems. These estuarine environments are constantly evolving, linked to sedimentary deposits of fluvial and marine origin. They present a gradient of physicochemical characteristics to which species must adapt. Knowledge of the different animal species, especially fish, that these rivers are home has always concerned the scientific community, which is convinced that fish and other fisheries resources represent the most accessible source of protein for the world population. In Africa, knowledge of the fish fauna of fresh and brackish waters has a very long history [3]. Currently just over 3 500 species of fresh and brackish water fish (95 families and 493 genera) have been described [4]. In Benin, studies that have looked at biological diversity have mostly focused on continental aquatic ecosystems [1, 5]. Studies on the faunal diversity of transition environments between fresh waters and marine waters are almost non-existent.

One of the transition zones between fresh water and marine water is the mouth of Cotonou which serves as a passage for several aquatic species which migrate from the Atlantic Ocean to lagoon Nokoué and vice versa. This mouth, which plays a very important role in the functioning of Atlantic Ocean-Lake/Lagoon Nokoué complex, has unfortunately, been studied very little in terms of biological diversity. This situation does not make it possible to develop an effective conservation and management policy for bio-aquatic resources of this environment in order to assess its impact. It is with this in mind that the present study on: “Fisheries diversity at the mouth of Cotonou” is intended to be a contribution to the knowledge of biodiversity at the mouth of Cotonou by providing a database on the physico-chemical quality water chemistry and a directory of fauna species at the mouth of Cotonou.

Specifically, it is:

– to evaluate the physicochemical parameters of the water at this location throughout the sampling period;

– to inventory the different groups of organisms transiting from the river to the sea and from the sea to the river;

– to determine the different indices which will make it possible to account for the number of species and the distribution of species sampled in this environment.

After the summary and the introduction, the different chapters constituting the document present respectively; the material and methods used; the results, discussions and a conclusion followed by some suggestions.

Materials and methods

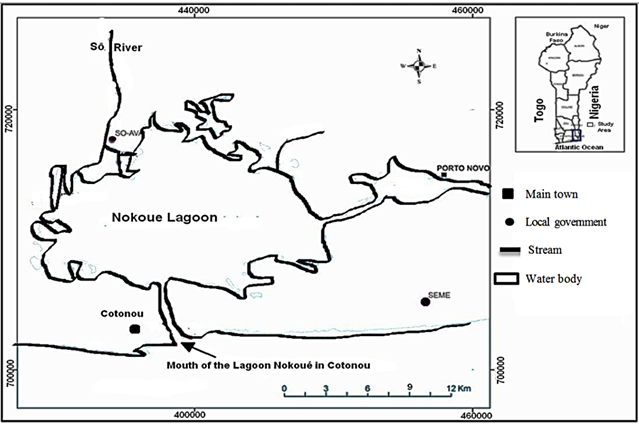

Study environment. Located in Benin in West Africa in the tropical zone between the equator and the Tropic of Cancer (between parallels 6° 30' and 12° 30' north latitude and meridians 1° and 30° 40' longitude Est) and more precisely in the coastal department, “the mouth of Cotonou” is the point where lagoon Nokoué, which normally covers an area of 150 km², meets the Atlantic Ocean through a channel called “Cotonou lagoon” (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Location of the zone shown by arrow

Like all places straddling two different natural environments, it is a place of great biodiversity: waters of different composition, temperature and speed meet. Nutrients and sediments carried by watercourses are diluted or deposited on the bottom.

Sampling during this work was carried out at 3 stations in this ecosystem.

Choice of sampling stations. The choice of sampling sites was based on a certain number of criteria such as the state of the bottom, the appearance of the water, the frequency of fishing activities and the depth (Table 1).

Table 1

Stations characteristics

|

Stations |

Longitude |

Latitude |

Observations |

|

1 |

2.44552 |

6.35767 |

Cluttered bottom and polluted water |

|

2 |

2.44490 |

6.35705 |

Frequency of fishing activities |

|

3 |

2.44411 |

6.35630 |

High depth |

Sampling method. Our prospecting took place from September 23, 2019 to May 7, 2020. During these 9 months, we carried out 17 fishing trips of 6 hours each, i.e. one fishing trip every two weeks including daytime fishing and night fishing. These captures were taken in both directions of water movement at each station (from logoon Nokoué towards the sea via the Cotonou lagoon and from the sea towards the chanel via the same lagoon) respectively direction 1 and direction 2. In each direction, the mass of water concerned circulates for 6 hours except in the event of heavy rain or a strong wave called “èhouèssou in Xlà language” which causes a delay of 30 minutes. Our sampling was based mainly on catches from artisanal and experimental fishing at our three stations on the front line of the mouth with still nets, cast nets, hook lines and creels. Aquatic organisms were collected and then labeled according to the station. Then, they were preserved with ice in a plastic cooler and transported to the laboratory of “Institut de Recherches Halieutiques et Océanologiques du Bénin (IRHOB)”.

Measurement of physicochemical parameters of water. Physico-chemical parameters such as dissolved oxygen, salinity, conductivity and temperature were measured using a YSI pro2030 multi-parameter model while pH was measured using a pH meter. type Milwaukee Ph600. Indeed, before taking each parameter, the probe was rinsed, calibrated then introduced into the water until a stabilization of the values was observed. These values were recorded on a sampling sheet and allowed data processing.

Species identification. Once in the laboratory, the well-labeled samples were identified to the species and measured using Quero and Vayne identification keys and guides, (1997) [6]; of the MRNF, (2011) [7]; Levêque C., et Paugy D., (2006) [2]; B. Séret., (1990) [8]; Wolfgang, (1992) [9] and Mbega, (2013) [10], FishBase, (2017) [4] and WoRMS [11]. Each specimen was measured and weighed using an ichthyometer and a low sensitivity balance respectively. Species difficult to identify were preserved with 70% alcohol in transparent jars. Species details were carefully observed under a binocular microscope.

Data analysis and processing. The taxonomic com-

position, abundance by taxon and total number of individuals were estimated for each of the sampled stations. The Shannon–Weaver diversity index (H’) was calculated for each station studied according to the formula:

H’= –Σ (pi · log2 pi),

where pi designates the number of individuals in the taxon / total number of individuals in the sample and log2 designates the logarithm to base 2.

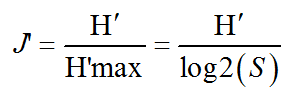

The Shannon index was accompanied by the Piélou equitability or equi-distribution index (J’) which measures the distribution of individuals within species, independently of species richness. It can vary from

0 to 1 it is minimal when a single species dominates the entire population.

Its value varies from 0 (dominance of one of the species) to 1 (equal distribution of individuals within the species).

,

,

where S – Specific richness; H′ – Shannon index.

The percentage of occurrence or frequency. Provides information on the environmental preferences (habitat) of a given species. It consists of counting the number of times the species “I” appears in the catches [5]. It is calculated as follows:

F = Fi / Ft · 100,

with Fi = number of landings containing species i and Ft = total number of landings made.

Depending on the value of F, three classes of occurrence were determined.

These are the species constants (F > 50%), accessory species (25 < F < 50%) and accidental species (F < 25%).

Results

Water physico-chemistry. The fish environment was characterized by the study of a few parameters such as temperature, pH, salinity and conductivity. The chi-square test applied to the matrix of physico-chemical parameters during our sampling campaigns showed a normal distribution of the parameters (P > 0.05) except for salinity which did not vary in direction 1. The values of physico-chemical parameters studied according to the direction, the station and the sampling period are recorded in the table below (Table 2).

Table 2

Average values of physicochemical parameters according to the stations and the sampling campaign

|

Stations, St |

Sampling |

Dissolved O2, mg/L |

Salinity, ‰ |

Conductivity, μS/cm |

Ph |

Temperature, °C |

Depth, m |

Transparency, m |

|

Serie 1 (Direction 1) |

||||||||

|

St 01 |

C1 |

6.02 |

0.1 |

248.4 |

7.7 |

29.6 |

2.0 |

0.36 |

|

St 02 |

5.98 |

220.2 |

7.8 |

3.8 |

0.55 |

|||

|

St 03 |

5.99 |

180.6 |

7.6 |

6.9 |

0.60 |

|||

|

St 01 |

C2 |

6.50 |

310.5 |

7.4 |

29.7 |

1.5 |

0.50 |

|

|

St 02 |

6.40 |

274.2 |

7.6 |

3.5 |

0.60 |

|||

|

St 03 |

247.0 |

7.8 |

29.8 |

6.4 |

0.62 |

|||

|

Serie 2 (Direction 2) |

||||||||

|

St 01 |

C1 |

7.58 |

16.4 |

26.67 |

8.2 |

30.1 |

1.5 |

0.40 |

|

St 02 |

7.33 |

16.1 |

26.45 |

8.5 |

3.5 |

0.56 |

||

|

St 03 |

7.15 |

15.9 |

26.21 |

8.1 |

6.4 |

0.62 |

||

|

St 01 |

C2 |

4.43 |

33.7 |

51.50 |

7.4 |

29.5 |

1.7 |

0.46 |

|

St 02 |

4.53 |

7.7 |

29.4 |

3.6 |

0.60 |

|||

|

St 03 |

5.12 |

7.1 |

6.7 |

0.66 |

||||

The temperature values obtained are between 29.4 and 30.1 ºC with relatively close values during periods of activity. The transparency and depth varied respectively from 0.36 to 0.66 m and from 1.5 to 6.9 m depending on the stations sampled. The pH values are between an interval of 7.1 and 8.5. Dissolved oxygen remained within a range of 4.43 to 7.58 mg/L. As for conductivity and salinity, they experienced very remarkable variations linked to direction (Sense 1 = = water coming from the lagoon towards the sea and Direction 2 = water coming from the sea). Conductivity oscillates between 180.6 and 248.4 μS/cm for direction 1 and between 26.2 and 51.5 μS/cm for direction 2. For salinity, the observed values remained constant at 0.1 ‰ in direction 1 and varied between 15.9 and 33.7 ‰ in direction 2. The highest values of salinity, dissolved oxygen and pH are observed in direction 2 while their lowest values are recorded in direction 1. Those relating to conductivity are high in direction 1 and lower in direction 2.

Diversity of the population. A total of 2 322 specimens belonging to 28 families, 32 genera and 34 species were recorded. Its individuals belong to three different phyla such as: Fish, crustaceans and mollusks. They are dominated by the order of perciforms as indicated Table 3.

Table 3

Composition of the fish fauna encountered at the mouth of Cotonou

|

Abundance* |

F, %** |

Occurrence class |

|||

|

Order |

Families |

Genera and Species |

|||

|

Perciformes |

Acanthuridae |

Acanthurus monroviae |

+ |

41 |

Accessory |

|

Carangidae |

Caranx hippos (Linnaeus,1776) |

||||

|

Trachinotus ovatus (Linnaeus, 1758) |

24 |

Accidental |

|||

|

Cichlidae |

Coptodon guinensis (Gunther, 1862) |

++ |

47 |

Accessory |

|

|

Eleotridae |

Eleotris senegalensis (Steindachner, 1870) |

+ |

24 |

Accidental |

|

|

Gerreidae |

Eucinomostomus melanopterus |

||||

|

Gobiidae |

Porogobius schlegelii (Gunther, 1961) |

29 |

Accessory |

||

|

Haemulidae |

Pomadasys rogerii (Cuvier, 1830) |

||||

|

Polynemidae |

Polydactylus quadrifilis |

18 |

Accidental |

||

|

Scombridae |

Scomberomorus tritor (Cuvier, 1832) |

24 |

|||

|

Serranidae |

Epinephelus aeneus |

18 |

|||

|

Trichiuridae |

Trichiurus lepturus (Linnaeus, 1758) |

24 |

|||

|

Lophiiformes |

Lophiidae |

Lophiodes kempi (Norman, 1935) |

18 |

||

Ending table 3

|

Taxon |

Abundance* |

F, %** |

Occurrence class |

||

|

Order |

Families |

Genera and Species |

|||

|

Siluriformes |

Claroteidae |

Chrysischtys nigrodigitatus |

+ |

29 |

Accessory |

|

Clupeiformes |

Clupeidae |

Ethmalosa fimbriata (Bowdich, 1825) |

++ |

53 |

Constant |

|

Pellonula leonensis (Gunther, 1869) |

+ |

24 |

Accidental |

||

|

Sardinelle maderensis (Lowe, 1838) |

+++ |

88 |

Constant |

||

|

Elopiformes |

Elopidae |

Elops senegalensis (Regan, 1909) |

++ |

53 |

|

|

Beloniformes |

Exocoetidae |

Cheilopogon melanurus |

+ |

35 |

Accessory |

|

Mugiliformes |

Mugilidae |

Mugil bananensis (Pellegrin, 1927) |

++ |

70 |

Constant |

|

Mugil cephalus (Linnaeus, 1758) |

59 |

||||

|

Neogastropoda |

Olividae |

Oliva flammulata (Lamarck, 1811) |

+ |

41 |

Accessory |

|

Decapoda |

Ocypodidae |

Ocypode africana (De Man, 1880) |

+++ |

88 |

Constant |

|

Peneidae |

Peneaus monodon (Fabricius, 1798) |

+ |

29 |

Accessory |

|

|

Penaeus notialis (Perez-Parfante, 1967) |

++ |

47 |

|||

|

Portunidae |

Callinectes amnicola |

65 |

Constant |

||

|

Callinectes pallidus |

+ |

35 |

Accessory |

||

|

Anguilliformes |

Ophichtidae |

Dalophis cephalopeltis (Bleeker, 1863) |

++ |

47 |

|

|

Ostreoida |

Ostreidae |

Magallana gigas (Thunberg, 1793) |

+ |

29 |

|

|

Pleuronectiformes |

Paralichthyidae |

Syacium micrurum (Ranzani, 1842) |

18 |

Accidental |

|

|

Sepiida |

Sepiidae |

Sepia officinalis (Linnaeus, 1758) |

12 |

||

|

Tetraodontiformes |

Tetraodontidae |

Chilomycterus reticulatus |

18 |

||

|

Veneroida |

Veneridae |

Tivela tripla (Linnaeus, 1771) |

35 |

Accessory |

|

* “+” – rare; “+ +” – abundant; “+ + +” – very abundant, %; ** F – percentage of occurrence.

Shannon's specific diversity and Pielou's equitability indices. The specific diversity (H’) and equitability (J’) indices recorded were relatively high with respective values of 4.06 bits/individuals; 3.63; 3.49 for (H’), and (J’) 0.85; 0.75; 0.69 (Table 4).

Table 4

Shannon-weaver diversity and Piélou equitability indices according to stations

|

Station |

|||

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

|

Shannon Specific diversity (H’) |

4.06 |

3.63 |

3.49 |

|

Pielou Diversity Index ( J') |

0.85 |

0.71 |

0.69 |

At each of the three stations, the Shannon specific diversity and equitability indices show no significant variation (Mann-Whitney test: p > 0.05). The more the specific diversity index (H’) is greater than 0, the greater diversity we have. The closer the Pielou fairness index (J’) is to 1, the more diversified the environment.

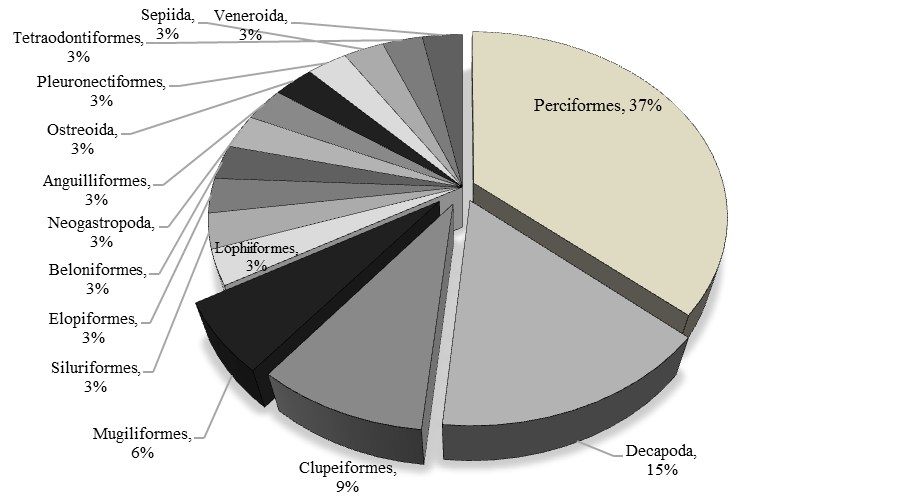

Specific composition. The current living organisms composition of the Cotonou Estuary is shown in Table 3. The order best represented in number of species in the waters of this environment is that of the Perciformes (12 species; 37%). This order is followed by the Decapoda with 5 species (15%), the Clupeiformes with 3 species (9%) and the Mugiliformes with 2 species (6%). The others orders (11) consist of a single species each (or 33% of all species) (Fig. 2).

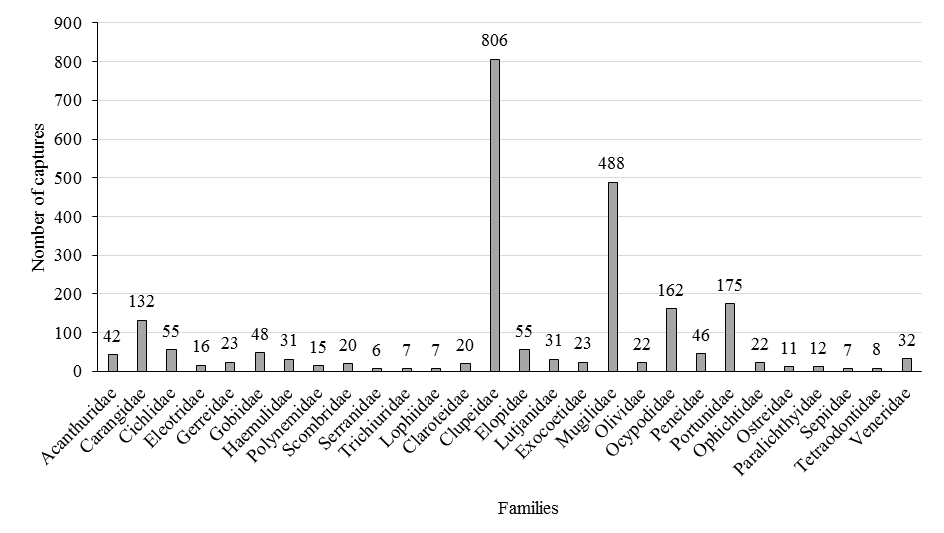

The distribution of the biomass of the different species presents two modes, the clupeidae 806 kg followed by the mugilidae 488 kg which constitute which live both in the sea and in brackish waters.

Fig. 2. Percentage in number of species of orders of fish caught in the waters

of the mouth of Cotonou between September 2019 and May 2020

After these last species, we can note the presence of the portunidae 175 kg which are crabs, followed by the carangidae 172 kg and the ocypodidae 162 kg (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Catches Composition by family

Discussion

The maximum depth of 6.9 m obtained differs from that of Gnonhossou [13] who obtained respectively at Lagoon Nokoué 3.4 and 1.4 m at Ganvié on the same lagoon complex. This can be explained by the advance of the sea and especially by the proximity of the study environment to the sea. In addition, the low value of water transparency recorded at our first sampling site in the two directions is due to pollution and dumping of garbage carried by the water of the lagoon from the Dantokpa market and its surroundings as noted by Baglo [14] which would increase the concentration of pollutants. Like the case of Kpétou and the semi-lake village of Guézin highlighted by Dèdjiho et al. [15]. This reduces photosynthetic activity. The temperature values obtained during this study are not contradictory to those of Lalèyè et al. [1] and Djiman et al. [16]. Indeed, the studies carried out by these authors show that the temperature of Lake Ahémé and lagoon Nokoué between 25 and 30 °C is a temperature range favorable to the presence of fish species from tropical zones.

The high oxygen content (6.5 mg/l) obtained in direction 1 where the lagoon water flows agree perfectly with the work of Gnonhossou [13] who stipulate that in the “flood” season: from August to November when salinity becomes minimal, the pH reaches these minimum values and dissolved oxygen reaches its maximum values. The measured contents also remained at their maximums during these flood periods. Then, the pH range obtained is favorable to the growth of fish species in accordance with the normal values specified by Boyd [17] and Kanangiré [18] which are between 6.9 and 9. A look at the variability of the pH shows that this ecosystem is slightly basic.

Furthermore, the low salinity value (0.1 ‰) constant throughout the flood period is mainly due to the inflow of water from rivers which are fresh waters diluting the salinity of the water in these places.

For the electrical conductivity of water, the highest value (246.81 μS/cm) recorded is far from Djiman et al. [16] who found a high conductivity value in the lagoon complex (11 700 μS/cm). This is a sign of an increase in the input of dissolved substances from the watershed.

The comparison of the results linked to the community of the Cotonou mouth settlements with those of other authors was not extensive due to the unavailability of results on this ecosystem. However, these results were interpreted and then compared with those of other lagoon ecosystems. Thus, the unequal distribution of individuals on the different stations is explained by the fact that each station is influenced by a type of factor which can be physical, chemical or anthropogenic. The low taxonomic abundance presented by station 1 could be explained by the presence of polluting elements coming from neighboring areas or activities carried out in the area.

Furthermore, the strong representativeness of Clupeidae and Mugilidae throughout our sampling respectively confirms the characteristics of marine fish Aqua Portail [19] for one and costal, amphihaline fish more resistant to climate change for the other according in the Biodiversity Atlas of Freshwater Lalèyè et al. [1] and Bhatt and al. 2023 [20] in this identification work of this genus. Sardinella maderensis despite the competition that exists between Sardinella aurita species was the only one crossed during the prospecting, a species tolerant of strong environmental disturbance compared to

S. aurita very sensitive to climatic variations despite a similarity in shape, activity and ORSTOM [21] diet.

The trends observed at the scale of our ecosystem for both diversity indices and numerical abundances may not exactly follow the changes observed at the general scale. However, it is important to highlight the limitations of diversity indices such as (H', J '). These indices do not take into account the size frequency of the species studied. Mature and juvenile fish do not occupy the same level in the food web and should, arguably, be considered different “species”. In addition, demersal species do not have the same probability of capture with the fishing gear used during sampling, which could exclude their presence in the catches and thus modify the specific composition of the surveys. These are synthetic indices.

Conclusion

This study made it possible to begin the study of the diversity of fauna of the mouth of channel of Cotonou. The hydrological regime of this ecosystem is influenced by the contributions of continental water from the fulvio-lagoon complex linked to lagoon Nokoué and those of marine origin. This causes a variation of physicochemical parameters of water and influences the distribution of species in this ecosystem. The inventory of this fauna made it possible to list a total of 2 322 individuals belonging to 27 families, 34 species distributed in three Phylum including fish, crustaceans and mollusks. Given the strong anthropogenic pressure, erosion and global warming, it is necessary to deepen the studies relating to the development and preservation of this environment on the one hand and to work in the direction of education and awareness of populations on the other hand. Given that this study is one of the rare ones on the biology of this environment, the results of these investigations will serve as reference data on the diversity of fishery products from the mouth and will enrich the national directory of aquatic fauna of Benin. We should note that the lagoon called before lake.

1. Lalèyè P., Chikou A., Philippart J. C., Teugels G. G., Vandewalle P. Study of the ichthyological diversity of the Ouémé River basin in Benin (West Africa). Cybium, 2004, vol. 28, pp. 329-339.

2. Levêque C., Paugy D. Fish in African continental waters Diversity, ecology, use by humans. Paris, IRD Editions, 2006. P. 566.

3. Paugy D. A historical review of African freshwater ichthyology. Freshwater Reviews, 2010, vol. 3 (1), pp. 1-32.

4. FishBase. World Wide Web electronic publica-tion.Available at: www.fishbase.org (accessed: 12.11.2024).

5. Vodougnon H., Lederoun D., Amoussou G., Adjibogoun D., Lalèyè P. A. Ecologic stress in fish population of Lake Nokoué and Porto-Novo Lagoon in Benin. International Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Studies, 2018, vol. 6, pp. 292-300.

6. Quero J. C., Vayne J. J. Delachaux and Niestlé. Marine fish from French fisheries: Identification, Inventory and Distribution of 209 species. Les encyclopédies du naturaliste. Suisse, 1997. P. 304.

7. Ministry of Natural Resources and Wildlife, MRNF. Guide to the standardization of ichthyological inventory methods in inland waters. 2011. V. I. P. 137.

8. Seret B., Opic P. Poissons de mer de l'Ouest africain tropical. IRD Editions, 1981. N. 49. P. 426.

9. Wolfgang S. Field guide to commercial marine re-sources in the Gulf of Guinea. Food & Agriculture Org., 1992, p. 268.

10. Mbega J. D., Teugels G. G. Guide to determining fish from the lower basin of Ogooue. Gabon’s agricultural and forestry research institute, 2013. P. 165.

11. WoRMS World Register of Marine Species. Available at: https://www.marinespecies.org/ (accessed: 15.01.2020).

12. Dajoz R. Précis d’écologie. Paris, Dunod, 2000. P. 615.

13. Gnonhossou P. The benthic fauna of a West African lagoon (Lake Nokoué in Benin), diversity, abundance, temporal and spatial variations, place in the trophic chain. Doctoral thesis. France, École Nationale Supérieure Agronomique de Toulouse, 2006. P. 141.

14. Baglo M., Worou T. Ch., Morakpaï C. S. Cotonou, Bénin. National Implementation Plan for the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants. 2007. June. P. 134.

15. Dèdjiho C. A., Topanou N., Gbaguidi G. J., Akpo E., Josse R. G., Mama D., Aminou T. Assessment of the physicochemical quality of wastewater tributaries of Lake Ahémé, Benin. Journal of Applied Biosciences, 2013, vol. 70, pp. 5608-5616.

16. Djiman L., Amoussou G., Vodougnon H., Adjibogoun D., Lalèyè P. Spatial and temporal patterns of fish assemblages in Lake Nokoué and the Porto-Novo Lagoon (Benin, West Africa). Fisheries & Aquatic Life, 2024, vol. 32 (1), pp. 9-25.

17. Boyd C. E. Water quality in ponds for aquaculture. Agriculture Experiment Station. Alabama, Auburn University, 1990. P. 482.

18. Kanangiré C. K. Effect of feeding fish with Azolla on the production of an agro-fish ecosystem in marshy areas in Rwanda. Doctoral dissertation. Presses Universitaires de Namur, 2001. P. 220.

19. AquaPortail: aquariophilie et biologie. 2007. Available at: www.aquaportail.com (accessed: 04.02.2020).

20. Bhatt D. M., Mankodi P. C. An annotated checklist of family Mugilidae Jarocki, 1822 (Actinopterygii: Mugili-formes), from India. Journal of Asia-Pacific Biodiversity, 2023, vol. 16 (1), pp. 5-19.

21. ORSTOM. Sea fish from tropical West Africa. ORSTOM. Field / Identification Guide 1981. IRD, 2011. P. 462.